Buried in Oblivion by Ron Jenkins

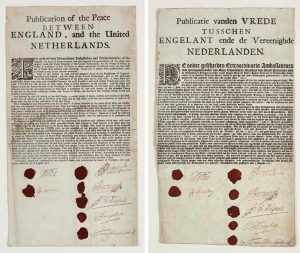

“… that all offences, injuries, and losses, which either side sustained, during this war or at any time, be buried in oblivion, and completely erased from memory, as if no such things had ever occurred.” –Treaty of Breda, 1667

“Forgetfulness is the world’s most dangerous disease.” ‐ Nobel Laureate, Dario Fo In 1667

“The Treaty of Breda” attempted to establish peace by formally obliterating the memory of war. The treaty, signed by England and the Netherlands, has been largely forgotten, but the document’s 350th anniversary gives us an opportunity to reflect on its legacy.

The treaty’s most substantive accomplishment was to give the English control of Manhattan in exchange for ceding the tiny spice island of Rhun to the Dutch. Rhun is now a forgotten speck of land in Indonesia’s Banda Archipelago, but in the 17th Century it was the key to the Dutch colonial empire. Rhun was the world’s primary source of nutmeg which at that time was worth its weight in gold. The battle for control of the nutmeg trade between the world’s reigning superpowers subjected the indigenous people of Rhun and other spice islands to death, slavery, rape, imprisonment, and genocide.

Our play was created to commemorate what might otherwise be forgotten about the Treaty of Breda and its legacy. The story is told from the point of view of the people that history has ignored: the inhabitants of the spice islands, who were the first victims of the Dutch Colonial conquest, but played an important role in the revolution that led to Indonesia’s independence in 1949. The idea for our play was suggested by the acclaimed Indonesian artist Made Wianta who, in 2012, proposed that we collaborate on a performance to mark the treaty’s 350th anniversary. He and his family brought me to Rhun where we met farmers, fishermen, imams and schoolteachers who told us their version of the island’s history. Their stories, along with other historic documents, like the 1621 testimony of a Dutch colonial officer and President Sukarno’s 1945 declaration of Indonesian independence, are the sources for our play’s text that you will hear performed along with sung verbatim excerpts from the 1667 treaty. These same sources informed Made Wianta’s artwork which inspired the design for our set.

The contributions of performers from several Indonesian islands have been central to the evolution of our production. Their extraordinary artistry is representative of the cultural diversity that can be found on Indonesia’s 17,000 islands and it is also reflects the experience of the slaves and contract workers who were brought by the Dutch to Rhun to work on the nutmeg plantations after most of the indigenous population had been massacred. An eighty-two year old nutmeg farmer named Kajiri told me how he and the other contract workers on the Dutch nutmeg plantations would gather at night to entertain each other with performances from their home islands. The Javanese workers presented shadow plays. The Balinese workers played makeshift gamelans. Acehnese workers performed their dances. In the face of hardship art helped the plantation workers keep their spirits free and stay connected to the traditions of their ancestors. During the centuries of struggle for independence, resistance to the Dutch occupation simmered under the surface of everyday life, like lava bubbling inside the volcano that dominated the spice island seascape. Made Wianta’s depiction of that active volcano is reprinted on the next page of the program and reimagined as the play’s central image. It is inhabited by the ancestral spirits who were never forgotten in Indonesia’s fight to overthrow colonial rule.

The Javanese, Acehnese, and Balinese dances choreographed by Dinny Aletheiani, Novirela Minangsari, and Nyoman Catra are rooted in island traditions that honor the memory of ancestors. These dances are performed as expression of indigenous freedom in opposition to the colonial oppression embodied by the treaty and its proposition that past injustices be “buried in oblivion.” Indonesian traditional performing arts have often been employed as a means of expressing political dissent. The onstage presence of an irreverent narrator, played by Indonesian master artist Nyoman Catra, echoes the iconic Indonesian character of the “penasar” who serves as a mediator between the world of the audience and the world of the play by setting the story in its historical context and commenting on its relevance to contemporary events. The gamelan music composed by Wesleyan Artist-in-Residenc I.M. Harjito evokes the ancestral past, providing a counterpoint to the Western choral music that Wesleyan Professor of Music Neely Bruce composed for the words of the treaty. In this context Bruce’s setting of the Bill of Right, performed as an epilogue, invites us to reflect on the modern relevance of the Treaty of Breda, which might be christened on its 350th birthday as the “Bill of Lack-of-Rights.”

Ron Jenkins – Director/Playwright

A former Guggenheim and Fulbright Fellow, Ron Jenkins has directed plays at Harvard’s American Repertory Theater, and in New York at LaMama, HERE, and the Provincetown Playhouse. His translations of works by Israeli playwright Joshua Sobol and the Italian Nobel Laureate Dario Fo have been staged at the Yale Repertory Theater, New York Theater Workshop, the Long Wharf Theater, and the Royal Shakespeare Company. Jenkins’ work as a playwright has appeared in festivals in Moscow, Bologna, Boston, Bali, Tokyo, and aboard a decommissioned World War II Destroyer in the Charlestown Navy Yard. Jenkins is also the recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Asian Cultural Council, the Watson Foundation, the Internet Archive, and the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities. He has been invited to writers’ residencies at the Atlantic Center for the Arts and at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center in Italy. Jenkins has engaged in theater research and practice in Indonesia since 1976 when he spent a year training and performing with a troupe of Topeng mask dancers in Bali. He is the author of several books on Balinese theater and published articles on Indonesian arts and culture in The New York Times, The Drama Review, the Jakarta Post, and the Oxford University Press International Encyclopedia of Dance. For much of the last decade Jenkins has collaborated with incarcerated men and women on the creation of theater pieces inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy. Sometimes assisted by his students from Wesleyan and Yale, Jenkins has staged these productions at prisons in New York, Connecticut, Italy, and Indonesia.